On Halloween of 2022, just weeks into the new school year, senior Ehni Ler Htoo was making his way through the halls of Proctor High School in Utica, New York, when a fellow student lurched at him from behind, repeatedly plunging a 9-inch hunting knife into his back.

Htoo managed to wrestle the knife away from his attacker, but not before sustaining deep lacerations to his shoulder, neck and hands. Responding officers “observed a large amount of blood pooling on [Htoo’s] stomach” and “blood strewn on the floor and walls,” according to a police report.

“All I know is my life was at risk, and I had nothing to do but fight for it,” Htoo said in an interview with ABC News. “I feel like I could have died during that situation.”

An attack of this nature — on school grounds, no less — would rattle any community. But leaders in Utica were doubly shocked, said former acting superintendent Brian Nolan, because the district had just invested some $4 million in an advanced, AI-backed security system designed to detect this type of weapon, made by a company called Evolv Technology.

“How does a student get a 9-inch knife into the school?” ABC News Chief Investigative Correspondent Aaron Katersky asked Nolan.

“He came in and he walked right through the Evolv system with his backpack,” Nolan said.

Evolv, in a statement to ABC News, said that its platform has a “proven ability to consistently detect a wide variety of threats” and broadly denied allegations made in a lawsuit brought against the company by Htoo.

But some critics characterize this incident and others like it as a cautionary tale — an example of the limitations of high-tech platforms, devices or software that claim they can deter or disrupt violence in schools.

“The reality is there’s not a great deal of evidence that many of the products being marketed would even work in an active shooter or other school security threat,” said Dr. Kenneth Trump, a veteran school safety consultant.

But that hasn’t slowed the growth of this booming industry. As violence in schools proliferates in the United States, so too has the marketplace for products designed to protect students. Today, school districts can purchase attack drones, white boards that turn into bunkers, and bullet-proof glass film, among a coterie of other high-tech products.

It’s a multibillion-dollar market, according to some estimates, and it’s expected to continue to grow as state legislatures pass or consider legislation mandating certain types of security hardware in schools.

No silver bullet

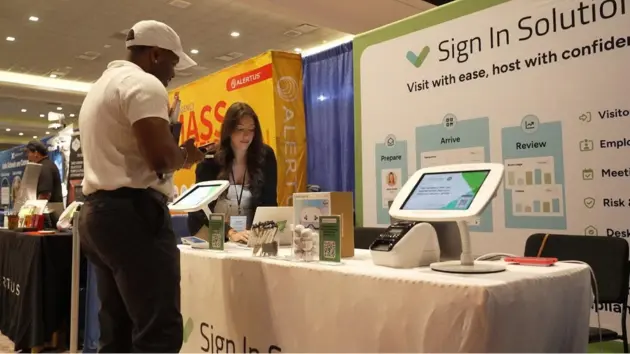

At a school safety conference in July, Curt Lavarello, the executive director of the School Safety Advisory Council and organizer of the event, said the industry has undergone a radical transformation in recent years.

“I’ve been in the school safety space for over 30 years now,” he said. “I remember coming to the conference where there may be four or five vendors. And now you see that we’re over one hundred.”

At his own conference, surrounded by panic alert systems and AI-backed weapons detection vendors, even Lavarello harbors some reservations about exclusively relying on products for school safety.

“I can’t say there is a silver bullet out there that is going to give us that 100% guarantee,” he said.

Among the new companies generating buzz across the industry is one that sells attack drones to school districts. Taylor Worthington, a company spokesperson, told ABC News that a drone pilot in a remote location can deploy on-site drones immediately and pursue a suspected shooter more safely and efficiently than first responders.

“We actually have the ability to launch pepper balls off of our drones,” Worthington said. “Worst case scenario, we can take our drones and run them at speed, 67 miles an hour,” into the suspect.

According to GovSpend, a data procurement database, K-12 public schools nationwide have spent nearly half a billion dollars upgrading their security infrastructure with various pieces of technology over the past five years. The industry’s value balloons to at least $3 billion when counting money spent by private schools and in higher education, according to another report from data analytics firm Omdia.

Some state legislatures have passed grant programs meant to help schools foot the bill for those upgrades, including in Texas and Florida, where mass shootings at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas in 2018 and Robb Elementary School in 2022 rattled the country.

Murky waters

In the aftermath of those high-profile incidents, school administrators say they feel immense pressure from their community to shore up the safety of their students and demonstrate that they’re taking steps to prevent violence from entering their schools.

“Every time, without fail, when there was a school shooting, within 48 hours I could count on a minimum of a half-dozen telephone calls from vendors huckstering all kinds of equipment to prevent something that everybody knew couldn’t be prevented with equipment,” said Dr. Rita Bishop, a former superintendent of schools in Roanoke, Virginia.

“I have to tell you,” Bishop said, “I’ve heard some pretty ridiculous proposals over the years.”

And critics say that all the public grant money swirling around the industry has fostered an environment ripe for some opportunistic actors to enter the market.

“Any time you influx a market with the kind of dollars that we’ve seen go to school safety … you’re going to have some murky waters, and you’re going to have to really look at who’s making those calls to the school district,” Lavarello said.

And despite the hundreds of millions of dollars school districts have spent to harden their buildings, some of these expensive pieces of technology have been cited in after-action reports for either not working as advertised — or not working when it mattered most.

In the aftermath of the 2021 Oxford High School shooting in Michigan, in which four students were killed, an investigative report commissioned by the school district highlighted multiple failures during the shooting — both human and technical — but also singled out their emergency alert system, called PrePlan Live, which it said “did not work as marketed” and “may have provided a false sense of assurance.”

The founder of PrePlan Live did not respond to ABC News’ request for comment.

After the Antioch School shooting in January 2025, Nashville’s school district said that a new AI weapons detection system, called Omnilert, failed to detect the gun used by an assailant who shot and killed two students.

Dave Fraser, Omnilert’s CEO at the time, told reporters that the platform “provides actionable information for staff and law enforcement to help them react to the situation, including knowing the exact location of the assailant.”

The Security Industry Association, a trade group that represents several companies in the school security space, told ABC News in a statement that “recent technological advances have made many security measures much more effective,” and that “it would be a mistake not to incorporate and fully utilize these improvements.”

But the group also acknowledged that “there are some products out there that fall outside wide acceptance among security professionals and deserve more scrutiny.”

“There is no single solution that alone will make our schools safe,” the group said.

The best line of defense

Regardless of what technology platforms a school enlists, experts overwhelmingly support investments in training staff on lockdown protocols, brokering relationships with students, and generating a community built on trust.

Officials in Wisconsin credited teachers for locking doors and shepherding children into classroom corners when a gunman opened fire at Abundant Life Christian School in 2024, killing three people and injured six. Officials said those basic steps likely saved lives.

“The first and best line of defense is a well-trained, highly alert staff and student body,” said Trump, the school security consultant. “When security works best, it works best because of people doing the day-to-day, basic, fundamental security measures that take place — reducing access to your building, greeting and challenging strangers, locking doors, knowing what to do in a lockdown quickly.”

During ABC News’ interview with Brian Nolan, the former superintendent in Utica, reports of yet another mass shooting on a school campus came in, indicating that a gunman had fired at students at Minneapolis’ Annunciation Catholic School, killing two students and injuring several others.

“It’s not lost on me that we’re talking on a day when there’s been a school shooting at a Catholic school in Minneapolis,” Katersky said. “Does that kind of thing still weigh on you?”

“It’s just a sad day,” Nolan replied. “We should never have to worry — this gets me upset — we should never have to worry about a child going to school and worrying about being killed.”

After the incident at Proctor High School, the Federal Trade Commission filed a complaint against Evolv, accusing it of “deceptive acts or practices … in the marketing and sale of security screening systems.”

The company settled with the FTC in late 2024 with no admission of wrongdoing. In a statement to ABC News, Evolv said the FTC complaint “was focused on historical marketing claims,” and that “since that time, our business has grown, and our marketing has evolved.” The firm added that, in 2025, they’ve “added more than three dozen new school districts as customers.”

The Utica school system still uses Evolv in several of its other school buildings. But Nolan’s experience has left him skeptical.

“In your experience, did the Evolv system make students safer?” Katersky asked.

“Absolutely not,” Nolan said.

Copyright © 2025, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.